I had been looking forward to Chapter 5 in Steven Johnson’s Wonderland to read about one of

my pastimes: playing games. The chapter starts out with a brief history of

Chess. The author uses chess to illustrate the main thrust of his book about

playing games. He writes: “[It is] one of the key ways in which the seemingly

frivolous world affects the ‘straight’ world of governance, law and social

relations. The experimental tinkering of games – a parallel universe where

rules and conventions are constantly being reinvented – creates a new supply of

metaphors that can be mapped on to more serious matters.” Such metaphors

include “raise the stakes” and “wild cards”. Alan Turing, one of the giants of

computing and A.I. wondered about whether machines can play chess.

No history of boardgames would be complete without mention

of The Landlord’s Game. According

to Johnson, the inventor Lizzie Magie “worked at various points as a

stenographer, poet and journalist… and was also a devotee of the

then-influential economist Henry George, who had argued… for an annual tax on

all land held as private property – high enough to obviate the need for other

taxes on income and production… Lizzie Magie appears to have decided that

radical tax reform might make compelling subject for a boardgame.” Thus the

ancestor to Monopoly was born, as can be seen from the 1906 picture of the

gameboard. I won’t repeat the story of how Clarence Darrow “invented” and

successfully marketed Monopoly; Johnson and many others have covered this.

The most interesting part of the chapter was on Games of

Chance. Johnson begins with astrigali,

a dice-like game that was the precursor to Backgammon. He then discusses

Cardano’s famous The Book of Games of

Chance where probabilities of dice rolls are discussed. Today, probability

and statistics have widespread use and a firm theoretical basis. Johnson,

though, ponders why it took so long to develop the basic theory of dice rolls –

after all, folks had been gambling over the centuries on dice-like games. He

proposes that “the answer to this riddle appears to lie with the physical

object of the die itself.” [Die is singular for dice.] Early dice were not

uniformly made, and were idiosyncratically biased. Johnson writes: “Seeing the

patterns behind the games of chance required random generators that were predictable in their randomness.

To think that the edifice of probability and statistics was

built on regulations placed on dice-makers forbidding the use of “loaded, mark

of clipped dice” because there’s always a huckster around the corner trying to

swindle you in a dice game. Hucksterism goes through much greater lengths in

today’s technological society, but that’s a different story. Johnson

writes: “By the time Cardano picked up the game, dice had become standardized

in their design. That regularity may have foiled the swindlers in the short

term, but it had a much more profound effect that had never occurred to

dice-making guilds: it made the patterns

of the dice game visible.” I even used these patterns when playtesting Bios Genesis to figure out how catalysts

were generated by rolling triples given N dice.

This month I finally cracked open the new version of Bios Genesis and played several games.

It had been over a year since I played, but I’ve been thinking about the

origins of life this month (subject of my next post) and found myself

sufficiently motivated. I did have to re-learn the rules again (they’re

complicated) but I can now show you some of the newer graphics and make some

comments about the game. To see the older graphics and read more about the

game, you can read this session report. The following pictures were

taken mid-game and I apologize for the blurriness. (My hands shake when I take

photos.)

Here are the event cards (shown above). One is drawn at the

beginning of every turn. We are three turns into the Archean Era, and are in a

Tropical Waterworld. A Huronian Snowball has just hit leading to new areas

where life may be seeded. (These are called refugia in the game.) Cosmic

refugia and Terrestial refugia are active as shown by the non-shaded meteorite

and mountains icons on the left of the card. The icons on the bottom panel

indicate what takes place. Two new refugia are revealed. Then there is release

of oxygen. (Organisms without protection against oxygenation of the atmosphere

are in trouble.) Finally the snowflake in the blue circle indicates that the

temperature is cold.

The two new refugia revealed are a Warm Pond and Eutectic

Brine. The cubes represent “manna” that can be used to generate catalysts (in

cycles!) and may form the seeds of chromosomal material if micro-organismic

life is able to take root. Dice rolls determine how the manna is cycled through

the system and if life can be “created”. The cube colors represent different

key constituents in life: red for metabolism, blue for genetics, yellow for

specificity (membranes), and green for managing entropy (i.e., increasing the

efficiency of energy transduction).

The overlaid pictures above show my bacteria that Amyloid

Hydrolysis bacterium that arose from the oceans. It has acquired ATP Synthase

and Chemiosmosis Respiration allowing it certain special powers as indicated by

the circled icons branching off the ‘helices’. I’m the Blue (Genes) player. My

organism is being parasitized by a Salmonella virus from the Green (Entropy)

player which is also equipped with Nitrogenase. Below is a picture of the Red

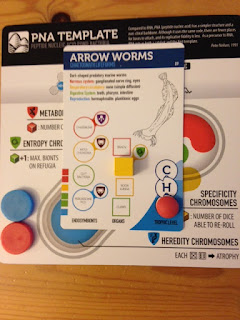

(Metabolic) player’s macroorganism, Arrow Worms.

Overall I like the new graphics, even though they took some

getting used to. It’s also nice to have actual cards on cardstock (rather than

pieces of paper). I think a game’s aesthetic increases the enjoyment in playing

– if it’s a good game. (If it is a lousy game, beautiful components don’t do

anything for me.)

I’ve found that over time, I enjoy games such as Bios Genesis more and more because they

are simulations that allow one to trace “what if” scenarios. I suppose it’s a

good thing I don’t play video/computer games because those could be much more

immersive environments that I might find hard to leave. Towards the end of his

chapter on Games, Johnson traces the development of SpaceWar!, perhaps one of

the first computer games. It had crappy graphics but being able to live-control those blips on the screen

drew folks in. As we think about machine intelligence and forms of A.I., games

have been the starting point. They also make the big news: Deep Blue versus

Kasparov, Watson versus Ken Jennings, and just two months ago AlphaGo versus Ke

Jie. But those algorithms also fuel scientific research delving into the

mysteries of conscious life. The boundaries of playing games and more serious

matters are increasingly blurred.

No comments:

Post a Comment