The brain is a fragile thing. It’s the first thing that

jumps out at me reading Eric Kandel’s The Disordered Mind. By examining the literature on brain disorders, Kandel,

a neuroscientist and Nobel prize winner, discusses how such fragility sheds

light on our minds – and perhaps what it means to be human.

Each book chapter links a disorder to some

characteristic of human function. The social nature of humans by examining

autism. Human emotions are explored by studying depression and bipolar

disorder. Schizophrenia sheds light on how we think and make decisions.

Dementia allows us to study how memory works. Connecting mind to motion is

studied through Parkinson’s and Huntington’s diseases. Addiction gives us

information about pleasure and choice. And of course, there’s the big unanswered

question: What is consciousness?

In today’s post, I explore Chapter 6 – Our Innate Creativity: Brain Disorders and

Art.

You’ve probably heard a story or two linking

creativity with mental illness. Kandel traces these ideas to 19th

century Romantic poets. While there are a number of celebrated instances of

famous artists who have exhibited some sort of mental disorder, correlation

does not imply causation. Kandel provides a quote from Rudolf Arnheim that

summarizes the main findings. “Present psychiatric opinion holds that psychosis

does not generate artistic genius but at best liberates powers of the

imagination that under normal conditions might remain locked up by the

inhibitions of social and educational convention.”

That being said, we do know some things about creativity

from a biological view. For one thing, it seems to involve the lifting or

removal of inhibitions. The left hemisphere of the brain responds repeatedly

when presented with a stimulus of some sort, for example an object to view. The

right hemisphere, on the other hand, responds only when the stimulus is novel.

Keep showing the same object and the right hemisphere gets ‘bored’. The

interesting part: Patients who develop frontotemporal dementia, a disorder “in

the left hemisphere [that removes] its inhibitory constraint over the right

hemisphere” develop otherwise unexplained creative impulses that previously may

not have existed. A different study on jazz pianists found that when

improvising, “their brain was damping down their inhibitions normally mediated

by the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex”.

When I was a kid, hearsay suggested that

left-handed kids were more creative than right-handers. (I’m a right-hander.) Left-handed

folks typically have a more active right brain hemisphere which, according to

Kandel, “is more concerned with putting ideas together, seeing new

combinations…” On the other hand, literally, us right-handed folks have more

active left hemispheres “concerned with language and logic”. Those are probably

sweeping statements referring to some sort of ‘average’ right-hander or

left-hander but I have not delved into the details. Apparently, there is

evidence that the left hemisphere inhibits the right hemisphere, and thus

damaging the left side releases these inhibitions.

Examples provided in this chapter are mainly about

artists and painters, although by extension you would expect writers, sculptors

and musicians to also be included in this category. The correlation between

artists and mental illness is what has been most extensively studied at this

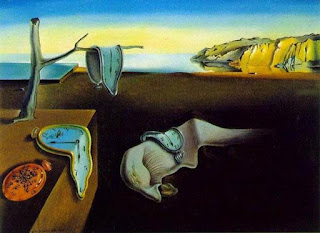

point. Kandel traces connections between ‘psychotic art’ to Dadaism and

surrealistic art – think Salvador Dali paintings. There is a mention of

economics Nobel Prize winner John Nash, made famous through the book and movie A Beautiful Mind. When asked by a fellow

mathematician how he could possibly believe he was being recruited by

extra-terrestrials, Nash responded: “Because the ideas I had about supernatural

beings came to me the same way that my mathematical ideas did. So I took them

seriously.”

In ancient Greece, the source of creativity came

from goddesses known as Muses. With brain disorders, could these be Muses of

Madness? I’ve occasionally been struck by wild ideas, dream-like in state. I haven’t attempted to enhance these experiences with psychedelic

substances. I don’t think of myself as particularly creative – but I feel I

have more creative ideas now than I did when I was younger. That seems backwards at first glance, but studies suggest that part of creativity involves

making freer associations between things you have learned as they incubate in

the unconscious. If you have little knowledge in a particular area, you’re

unlikely to exhibit creativity in that domain. I’d like to think that as I have

pondered chemistry more deeply, while widening by breadth of knowledge in other

areas, that I’m at least capable of increasing in creativity of thought. I also shouldn't forget that creativity can encompass both the technical and entrepreneurial.

One thing I do fear is losing my mind. Reading the

afflictions of those with mental disorders is troubling because the brain is a

fragile thing. How the brain embodies the mind (or is it the other way around?)

is an enigma – one that is unlikely to be solved only by neuroscience.

Certainly, mind and brain are closely connected, and the fragility of one manifests

in the fragility of the other. That being said, I’m amazed at how robust human

minds can be. From abstract thoughts to how sights and smells conjure memories,

half-baked and re-baked with each retrieval, some embellished while others fade

away. How we teeter on a knife’s edge between sanity and madness.

Below: Salvador Dali’s “The Persistence of Memory”

No comments:

Post a Comment